Firewalls can't protect today's connected cars

- 25 July, 2015 01:12

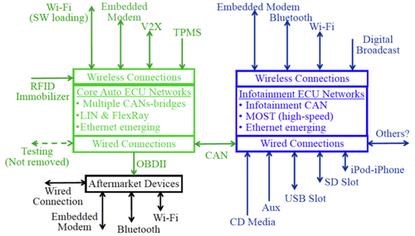

This diagram shows more than a dozen wireless access points to a vehicle's head unit and controller area network (CAN).

The Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu once wrote, "What is of supreme importance in war is to attack the enemy's strategy."

The automobile industry needs to follow Sun Tzu's advice to secure increasingly connected vehicles from hackers, according to experts.

Instead of building firewalls to keep cyber attacks out, which industry watchers say is ultimately a futile endeavor, build systems that recognize what a security breach looks like in order to stop it before any real damage is done.

"If you hack into my car's head unit and change the radio station, I don't care. I can live with that," said Charlie Miller, one of security experts who this week demonstrated they could hack into -- and remotely control -- a Chrysler Jeep.

"If you can hack into my head unit and make my brakes not work, then that's a different story. Let's stop the attack after they're already in," Miller said.

It's called operational security, and the auto industry -- even the banking industry -- has been slow to adopt it, according to Egil Juliussen, a senior analyst and research director for IHS Automotive. "They assume hackers can't get through their perimeter security, which is not true," Juliussen said. "That's a basic principle for security."

The auto industry got a wake-up call this week when Miller and Chris Valasek showed how they could hack through the perimeter security and into an early model Chrysler Jeep's UConnect head unit, also known as an infotainment system. Previously, hackers could breach a vehicle's internal computer bus only by physically connecting to a car's onboard diagnostics (OBD-II) port.

Miller and Valasek demonstrated that by using the vehicle's cellular network connection, they could wirelessly talk to the Jeep's head unit, and then access the Jeep's control area network (CAN).

All modern vehicles have a CAN, which acts as a computer superhighway to the vehicle's various electronically controlled components. Once on the CAN, Miller and Valasek discovered which electronic messages controlled various systems, and they were able to send messages to remotely control the brakes, transmission, acceleration and other vital components.

As cars become more connected to other vehicles, surrounding infrastructure and to manufacturers and their parts suppliers, the ability to breach a vehicle's security will only become easier.

With self-driving, connected cars comes greater risk

And, as autonomous functionality -- even fully self-driving cars -- emerge, it will mean that protecting computer systems from attack will become more crucial.

At the same time, car makers already remotely collect data from their vehicles, unbeknownst to most car owners, in order to alert the drivers to needed repairs or maintenance and for future research and development.

According to Nate Cardozo, an attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, "Consumers don't know with whom that data is being shared. Take the Ford Sync, for example. In its terms of service, it says it's collecting location data and call data if you use Sync to dictate emails."

Sync is Ford's current Microsoft Windows-based telematics or head unit system. The company is changing over to a QNX-software based system this year.

Miller and fellow hacker Chris Valasek shared their year-long efforts with Chrysler, which issued a software patch to fix the security hole in the head unit. Vehicle owners must download the patch onto a USB drive and then update the vehicle's software with that.

But Miller warned that while Chrysler may have fixed this specific remote flaw, "there are probably others."

"I don't think there's a way to you can make a really secure way for computers to communicate," Miller said. Hacking a network firewall simply takes time and perseverance.

The CAN bus is very simple and the messages on it are very predictable, Miller said. "When I start sending messages to cause attacks and physical issues, those messages stand out very plainly. It would be very easy for car companies to build a device or build something into existing software that can detect CAN messages we sent and not listen to them or take some sort of action."

Juliussen agreed.

Once past a firewall, hackers can make computers imitate any other computer on a network, and that means they can control the systems through electronic messaging. That's basically what Miller and Valasek did: They had the head unit pretend to be the electronic control unit (ECU) for the brakes, the transmission and other systems.

Behond the security curve

Carmakers are far behind the security curve, not only because vehicles have an average six-year development cycle, but also because they haven't taken the potential security problem seriously.

"The automobile industry has been slow to do anything. I did my first presentation [at an auto industry conference] five years ago and they said this very interesting, but we don't need it yet," Juliussen said.

For example, in response the hack on Chrysler's UConnect head unit, Ford issued a statement claiming its communications and entertainment systems feature a different architecture than what was hacked. "Our vehicles have a hardware based built-in firewall that separates the vehicle control network from the communications and entertainment network," Ford stated.

Ford declined further comment and didn't say whether its Sync head unit and coming QNX-based unit can detect errant messages that could indicate a cyber security breach has occurred -- and then shut it down.

Miller said he can imagine a more secure method, such as using cryptography or encrypted messaging within a vehicle's CAN, to make it more difficult to hack.

But, if an attacker has physical access to a car, they can get access to the firmware on various computer chips and figure out what the encryption keys are, Miller said. "Every car isn't going to have a different key," he said, referring to the fact that once one car is hacked, all the models are vulnerable.

A detection system versus a better firewall

Instead, both Miller and Juliussen said, car companies could "easily" build a separate computer to detect errant messages. The computer would watch the messages that flow between a vehicle's computers or electronic control units (ECUs), and use a database to determine which messages are authentic.

For example, Isreal-based Argus Cyber Security Ltd. is a start-up that sells detection software for the connected car industry. Argus's Deep Packet Inspection algorithm scans all traffic in a vehicle's network, identifies abnormal transmissions and enables real-time response to threats.

Both Miller and Juliussen believe in a layered approach to security. Hardware-based encryption with cyber attack detection is the most promising for securing the future of the connected automobile, they say.

Yet, much of the auto industry's efforts already underway are around building a more secure bus than today's CAN specification.

Ethernet is joined by about a half-dozen other in-vehicle communication protocols, such as LIN (Local Interconnect Network), MOST (Media Oriented Systems Transport) and FlexRay -- aimed at increasing bandwidth to and from the car as vehicle monitoring systems become more sophisticated.

Vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) and vehicle-to-retail (V2R) will be two of the most dominant segments of the connected automobile market over the next decade or more, analysts predict. By 2030, more than 459 million vehicles will support V2I and 406 million will support V2R, according to ABI Research.

Others advocate for different security approaches. Ken Schneider, vice president of technology strategy at software security company Symantec, believes digital certificates -- a digital handshake between computer systems -- will be key to providing privacy while also allowing crucial driving data to be gathered. The data will help local governments and auto manufacturers improve overall traffic conditions; the individual driving experience can use data that comes from a vehicle's internal computers.

Modern vehicles, Schneider said, can have as many as 200 ECUs and multiple communications networks between internal computer systems. While most systems are isolated within the car, others are used to transmit data back to manufacturers, dealers or even the government.

"On the plus side, this data can make the user experience much richer and personalized because from one vehicle to the next, it will know all my settings and [be] able to integrate your car into your digital day," Schneider said. "The flip side of that is it creates risk."