Understanding Google's Alphabet structure (think, alpha bet)

- 14 August, 2015 03:57

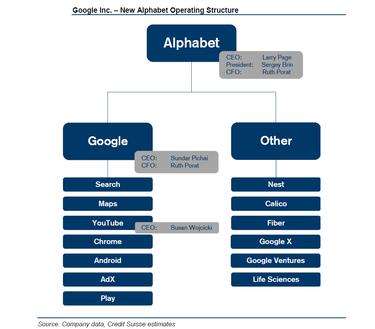

Splitting the name of Google's new holding company Alphabet into two "alpha" and "bet" may help explain the new business structure that JP Morgan analyst Doug Anmuth called "an elegant way for Google to continue to pursue long-term, life-changing initiatives while simultaneously increasing transparency and management focus in the core business" in a recent report.

Alpha is "investment return above benchmark," noted Larry Page in the company's announcement of the new name and structure on its new website, abc.xyz. The word "bet" could refer to all the long-term bets Google has made in a spectrum of big ideas some would call them moonshots including driverless cars, life sciences, home automation and robots.

The new company's core (alpha) businesses such as search, maps and YouTube will still be called Google. Sundar Pichai, who was promoted to CEO as part of the announcement, will report the results of Google's operations separately beginning in Q4 2015. The moonshots, the "bets," will also be reported separately.

As Alphabet CEO Larry Page mentioned in his blog post about the restructuring, Google has a track record of successfully launching products that are now used by billions of people (YouTube, Google Maps, Android, etc.). Alphabet looks like a new innovation management and finance model, a formal approach to incubating businesses into large-scale operations.

Separation anxiety?

You can imagine that Page and cofounder Sergey Brin are passionate about the many moonshots incubating under the old Google corporate structure. But large cap investors might find them an unprofitable distraction from the core revenue and profit-producing business in which they invested. Fund managers with perspectives narrowed by the necessity of quarterly earnings expectations can't model and place a value on projects like the autonomous car. Those kinds of moonshots could require large loss-making investments during a five year or longer horizon to bring to market and become accretive to Alphabet's earnings.

[Related: Don't look for Google to make big, quick changes after Alphabet pronouncement]

Pleasing large cap investors with Alpha investment results and betting on new businesses to find the next big growth area do not coexist comfortably with one another. According to Page, the price of comfort is reducing growth expectations to incremental change. Emphasizing the dilemma, Page said "in the technology industry, where revolutionary ideas drive the next big growth areas, you need to be a bit uncomfortable to stay relevant."

Stanford economics professor Nicholas A. Bloom explains how Alphabet will make investors comfortable: "There are two benefits of the new structure. One is visibility, in that with the split it makes it easier to model the main search business from the distracting moonshots. The second benefit is it contains the moonshots, because as separate businesses it is much harder to fund them under the radar. Fund managers were nervous about Google tunneling cash from the search business to other long-shot ventures unchecked, and with the Alphabet model they cannot do this. Google has put constraints on how much its founders Page and Brin can fund moonshots, and the market not surprisingly likes this."

Good fences make good neighbors

Last quarter and consistently throughout the company's history over 90 percent of Google's revenues have been produced by its search advertising and Google sites businesses including Google Play and YouTube.

In a report about the new structure, Nomura research analyst Anthony DiClemente underscored the idea that increased transparency should increase shareholder value. "Investors have long desired better visibility into the trends and profitability of Google's core business outside of investments in more speculative projects like Google Fiber, Project X and Calico," DiClemente said. "Under the new structure, opex investment in these more long-term investment initiatives will be excluded from Google's reported results, providing investors a clearer picture of the core businesses underlying trends."

[Related: Google restructuring could rein in business 'chaos']

DiClemente's report pointed out that investors can value the core business's revenues and profits without the drag of investment in the moonshots. They don't value the potential big growth areas as much as understanding the amounts that Alphabet will invest in incubation.

"What we don't yet know about Alphabet may be the most interesting," says Harvard Business School professor of entrepreneurial management Thomas R. Eisenmann. "Alphabet could finance the moonshots' growth by selling equity (called tracking stocks and letter stocks) that restricts the new investors ownership to just a moonshot business or segment and wouldn't consume any of the $68 billion of cash on Alphabet's balance sheet. Management's necessary long-term horizon for these businesses might also be protected by issuing shares to new investors with proportionately fewer votes per share like the original Google initial public offering." It seems like ancient history now, but new outside investors in Google received one vote per common share, compared to the 10 votes per share held by founders and venture investors, which left existing investors in control," he says.

If adopted, Eisenmann says, "This new capital structure would naturally sort investors based on risk and reward."

With access to outside capital as described by Eisenmann, the incubating moonshots have a better chance to become high-growth businesses like YouTube, Google Maps and Android without making large cap investors uncomfortable. And if all goes well, some of Wall Street may value Alphabet more on transformative expectations and growth than just revenues and profits like it has for near-profitless Amazon and profitless Tesla.